In Fellini’s late-career 1972 film Roma, the director, who appears as himself in one segment, speeds around his beloved city at night with a camera crew and in the worst weather; and at the end of the film sends a troupe of motorcycle riders on a noisy frenetic tour past the city’s great sites.

He portrays his childhood city Rimini and his young man’s Rome with their street dinners and brothels and Fellini grotesques, and gives a kick in the pants to the church, with a wicked fashion show of sacerdotal attire.

It’s 1972, after all, and so hippies are present, smoking dope and just sitting around, being moved violently on from the eternal architecture at one point by baton wielding police.

The film elicited hippie culture, because it had to in those days, the way Raymond Burr’s Perry Mason episodes and later 1970s TV series portrayed the Beats, hippies and a gaggle of troubled teens.

Spanish director Luis Garcia Berlanga also had fun with hippies in his 1970 Long Live the Bride and Groom, where the muddled hero can’t keep his eyes off Berlang’s version of the trope: Swedish girls in bikinis attended to by long haired guys.

For these directors, hippie culture was just another element of the eternal bizarre, the everlasting bazarre, so well represented historically by Rome, specifically its deterioration politically from a republic to a dictatorship and its rise and fall in power as an empire. Like the American empire it pretended it wasn’t. Octavian Caesar allowed the senate to continue sitting as if they and the people had a voice in a representational government, but of course they did not — they became the toga-ed rubber stamp for the Caesars.

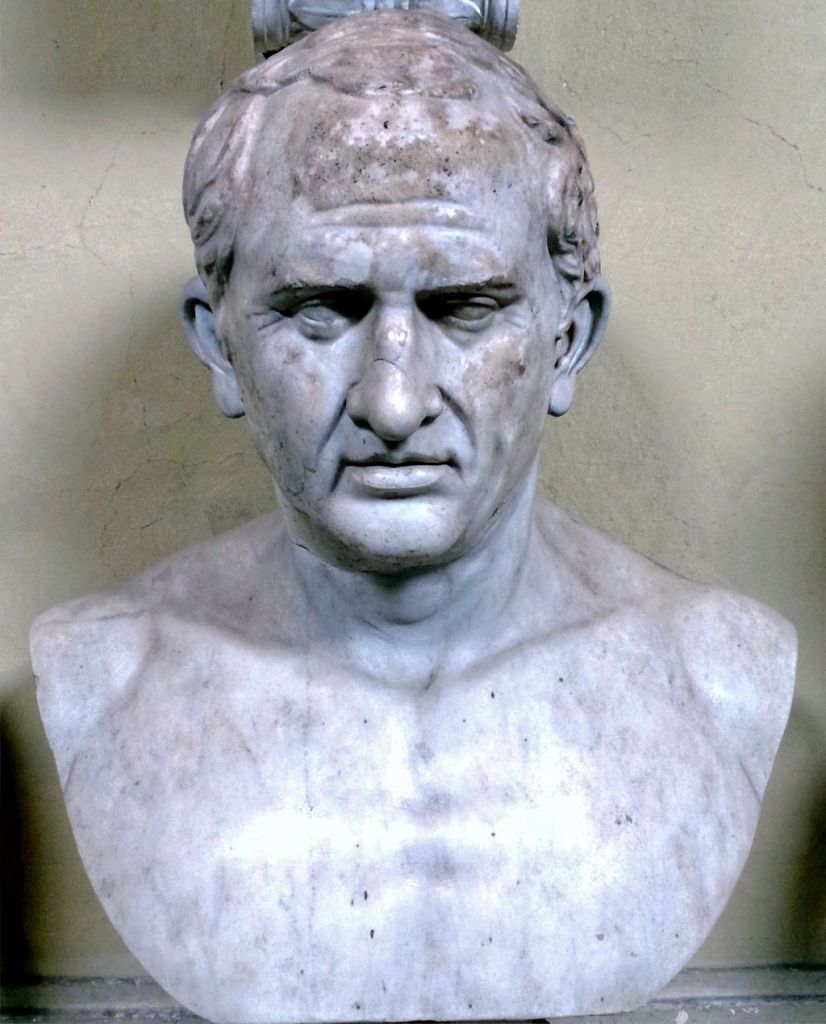

The Authorial Rabbit has been reading two historical fictional accounts of the life of Chickpea, that is to say, Cicero, the great orator of Ancient Rome, and finds, as others have, the clear parallels between Cicero’s time and our own, in our (that is to say American but not restricted to the USA for it is a western democracy affliction) Trumpian Nero-like decline.

There is solace and resignation in recognizing that the best and worst are our enduring human heritage.

American Steven Saylor’s Catalina’s Riddle (1993) uses his frequent narrator detective Gordianus the Finder to show us the pre-Christian era times of Rome and Cicero’s role in the take down of rogue senator Catalina, whose attempt to shake up the Republican Party-like strangle hold on money and power of the ruling and rich Optimates of the Roman republic ended in illegal executions perpetrated by Cicero. Cicero’s hastiness to convict and kill, even in support of a republic rather than the dictatorships to come, would be his own downfall eventually.

The first volume of Britain’s Robert Harris’ Cicero trilogy, Imperium (2006), charts Cicero’s development from lawyer to crafty and not always principled statesman. His portrait of Catalina is less glowing and sympathetic than Saylor’s. Catlina has always been controversial among historians. Harris paints him as charismatic with no governing experience or skill and a serious anger management problem, the products of which are of an ancient Rome degree: raping a Vestal Virgin, gouging out eyes and ripping out tongues, and so on. He conspires with rich noblemen and the budding tyrant Julius Caesar to overthrow the republic, ostensibly to introduce land reform but really just to gain power.

The Roman Empire did decline and fall. Yes, it was eventually overrun by outsiders. But the great city of ancient Rome, home to one million people at its peak, became a wasteland of 10,000 desperate souls by the sixth century AD not because of outside invaders. It was destroyed from within. As its administration became more corrupt and incompetent, with emperors turning over at an ever faster rate, often dispatched by the military, Rome grew less productive, less able to provide for itself, almost completely reliant on foreign resources.

One thinks sadly of the great city of Buenos Aires as a visible example today of the phenomenon of decline from within, and not the only one. To walk its streets today, as the AR has done many times, is to weep among its decayed once-beautiful architecture, its potholed sidewalks and streets, its graffiti, its malfunctioning systems, its relentless inflation, its slums and armies of the poor searching for cardboard and other scraps at night. Its less visible but assured cause is lack of trust: in institutions, the rule of law, in people with whom you disagree. Only the tribe is right and its rightness is absolute and any means of protecting it, including the Peronist “Build the Fatherland, Kill a Student,” is justified.

The Atlantic‘s David Frum has penned an insightful article on such a decline. He alludes to Argentine and Peron, who is as perfect a model for Trump as history holds, as he warns of the increasing acceptance of violence against domestic enemies among the Trumpites, young and old, the new fascism, American style. The ends justify the means for the tribal haters. Any action, no matter how horrific, can be justified in such a time. And because freedom can be defined in such a time as not cooperating with other tribes to maintain infrastructure, healthcare (and COVID response), the environment, schools, courts, building codes, transportation, a free press — all the structures of a healthy community — it is a freedom to perish.

Visit Rome and observe this freedom among the ruins. Walk the ancient Forum. Meditate upon what was built with great hope and daring and ingenuity and no little hubris. Meditate upon the dust.