*****

“Depressed?”

“No, certainly not. Not at all.”

“Finished?”

The Doe I Know (DIK) lays her hand on my furry shoulder, rubs my long ears. “It’s gone,” she consoles. “The cycle continues. Let it go. Remember the Tao.”

The Authorial Rabbit lumbers about the family nest, staring upward through the entrance hole at the dark winter sky, the swirling black clouds, downward at roots and stones, stores of carrots.

The AR phones Titmarsh. “It is done.”

“Good on you! What’s next?”

Silence on my end of the line.

“No clue?”

“None.”

“The world will be bereft. Summer was past and the day was past.”

Titmarsh is Frost-y, wry — and Tao-ish. He quotes Stephen Mitchell’s translation of the Tao Te Ching:

Do you have the patience to wait/till your mud settles and water is clear?/Can you remain unmoving/till the right action arises by itself?

Evidently not. I call K. No answer. Strange beeping, a hissing on the line.

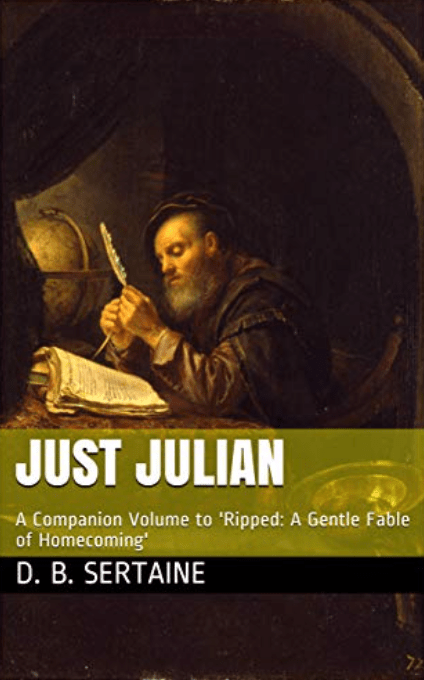

Anyway, the AR’s new book, Just Julian, is now on Amazon. It’s a sequence of a sort for Ripped: A Gentle Fable of Homecoming, from back in the day.

Currently reading Lafcadio Hearn’s ghost stories from Japan. In one tale, a blind minstrel, a bard, is temporarily sheltered in a monastery, where his friend is a monk. One evening, when his friend has gone out and he is alone, he hears heavy footsteps on the walk. A mighty samurai has come into his room, he hears the sound of his armour.

“Come,” orders the samurai in a powerful aggressive voice.

“What? Come where?” cries the blind minstrel.

“To my lord’s court, to play for him the song of the great battle of our people against their enemies.”

The blind minstrel is known for his rendering of a fatal battle between two powerful clans, one of the clans completely destroyed, every man, woman and child.

Reluctantly, the minstrel lifts himself up, wraps his lute, his biwa, goes with the warrior. The warrior grips his arm from time to time. The journey is long, the path is winding and rough. Eventually they reach what he senses is a massive gate. The samurai calls out for entrance. The minstrel hears the gate open. They go in. Again, a long path, the bard hears water, smells the fragrances of the night.

They reach a doorway. On the other side the minstrel hears noises of a court, courtiers, gossiping, bragging. He is led in and the room goes quiet. From ahead of him a mighty voice greets him, the lord, acknowledges his fame, asks him, requires him, to sing of the fatal battle.

The minstrel sits, strums and begin his song. He senses the hushed expectation of his audience. For two hours he plays and sings. At times, he hears sobs, the movement of garments, even the slumping onto the floor of warrior limbs.

When he is finished he is touched lightly on the shoulder by the warrior who guided him to the court. “It was fine, very fine. Now you go, we return tomorrow and every night, until it is finished.”

The minstrel does not want to return to this place but he nods and they walk long and he arrives at the monastery near dawn, for he hears the birds. No one has noticed his absence.

The next night the samurai visitor comes again and the two walk to the lord’s court, where the minstrel again plays and sings the story of the fatal battle. The same sounds of a deeply moved audience.

And the next night. And the next night.

On the last night when the minstrel reaches that part of the tale where one of the clans is completely annihilated, the audience shrieks, wails, pounds fists on the floor. The minstrel has never heard such sorrow.

This time he has been missed at the monastery. His friend the monk sends attendants out to search for him. They rush out into the night. They search through the forest, along every pathway.

They reach a cemetery, and are surprised to see in the darkness the blind minstrel sitting upright among tombs strumming his biwa. Alone. There is no one anywhere around him. No soul anywhere, only the memorials of the dead.

“Come home,” the attendants cry, hurry, hurry, and they guide him home running.

At the monastery, his friend upbraids the blind minstrel. “You must never go out at night alone. It is dangerous. I don’t like these visits. There are wicked ghosts about.”

The monk decides to protect his friend. Chanting, amongst incense, he inscribes magical scripts on the minstrel’s body, everywhere, almost, even the soles of his feet. “You must not move tonight, not a muscle, no matter what you are asked. If a visitor should come. No movement, no matter what!”

That night as the minstrel sits in meditation on his mat in the monastery, his biwa at his side, he hears the familiar stride. The rice-paper door slides open. The minstrel sits unmoving, barely breathing.

The voice.

“Ah,” its says, angry. “I see only two ears. Two ears floating.”

The monk feels a strong hand on each ear, pinching, painful, pinching, tighter and tighter. The monk does not flinch. The warrior hand tears the two ears off, rips them completely off. Despite the ingratiating pain, the monk does not move, remains upright in the meditation posture, does not cry out.

The samurai waits, before seeming to acquiesce. And he is gone.

The next morning the monk finds his friend barely conscious, still straight upright in meditation, his face a mask of suffering, the terrible torn ears, blood running down the sides of his face, permeating the tatami mat.

The monks and attendants care for the minstrel. In time his wounds heal. His friend sorely laments that he missed the minstrel’s ears when he was inscribing the protective scripts, but the minstrel does not blame him.

The minstrel lives a long life. Always thereafter he is known as the Earless Bard.

The AR rubs his ears. Those at least are still with him.