Titmarsh has rushed over. He warned me he would come. He has that smug, complacent look, which means he intends to one-up the Authorial Rabbit.

We sit in the back yard, distanced, one wine bottle, two glasses, the sun beaming down on our hairy faces in our cushioned chairs, our eyes for the moment closed.

Squirrels, raccoons, sparrows, finches, creepers, the neighbour’s cat — play in the bushes and trees. Rabbits, apart from yours truly, are sleeping, for afternoons are nap time. Normally. When there are no guests. A cicada sings. High above, a crow articulates his pragmatic view of the world.

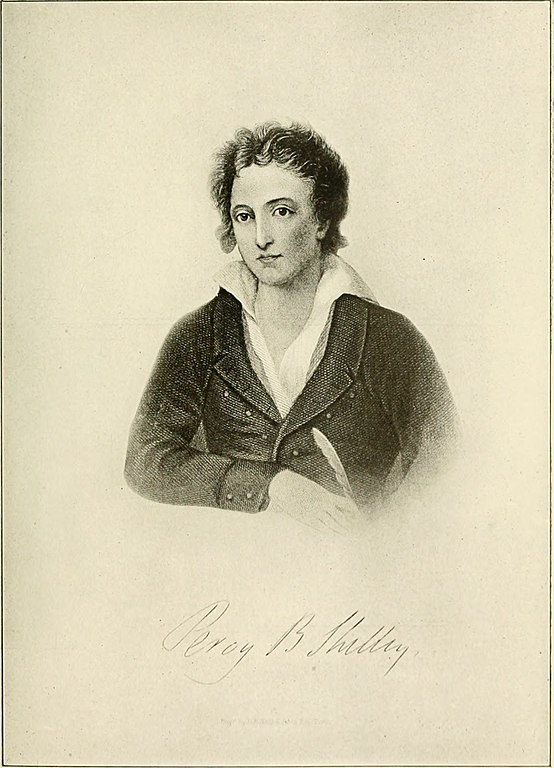

“Shelley,” croaks Titmarsh, nearly choking on his wine, so much pleasure does have in expressing the syllables.

“A relation?” asks the AR.

Titmarsh smiles in forgiving sympathy. I hear the rustling of a raccoon in the hedge and realize our words are being monitored.

“Percy Bysshe Shelley.”

“Ah, your poet.”

“Not Keats. For once.”

“Ah. No. Shelley. Yes. Your great friend. Drowned. Too young.”

Titmarsh rises, sets down his glass. I am in for it.

The One remains, the many change and pass;

Heaven’s light forever shines, Earth’s shadows fly;

Life, like a dome of many-coloured glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity,

Until Death tramples it to fragments.—Die,

If thou wouldst be with that which thou dost seek!

Follow where all is fled!—Rome’s azure sky,

Flowers, ruins, statues, music, words are weak

The glory they transfuse with fitting truth to speak.

Titmarsh sits down, looks around, perhaps expecting applause from the gathered creatures.

“Beautiful. Truth is beauty,” I say, alluding to Keats, just to set the record straight. “He died in Rome.”

We both ponder mortality. I sing, “‘He has awakened from the dream of life, ‘the mad trance. Cold hopes swarm like worms within our living clay.'”

That may take some of the steam out of my dear friend. Indeed, he shudders.

I continue. “”Tis we, who lost in stormy visions, keep/With phantoms an unprofitable strife.'”

“The point is . . .” he begins.

I lean in, not too close. My friend is sensing the tide is turning, our strife is is decaying. He smiles.

“Of course,” he concedes.

The sun’s light forever shines. What a good friend he is.

“Peace,” he says and sips on his wine.

“May we have it now, not be lost in ‘stormy visions,’ not wait for eternity.”

“Yes.”

We sit quietly.

“A habit of mind,” I suggest.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Unlikely to arrive on a thunderbolt,” I say. “Just bits, day by day, reminding ourselves regularly, even as the old occupant tries to build its walls.”

Titmarsh grasps my lesson, that the struggle to accept the consciousness of eternity, that consciousness beyond the individual ego, is usually, not always, but usually, a slow road. Narrow is the gate and straight is the way, as another tradition puts it.

We sip our wine. A crow speaks in the trees.