“The novel is going how?” asked Titmarsh of the Authorial Rabbit. Titmarsh was not cruel but he had obsessions. The AR’s output was one. Easier than dealing with his own.

“Coming along, coming right along,” I replied.

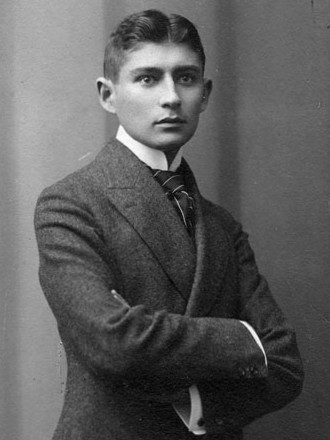

“Franz Kafka has just published a new story in the New Yorker and he’s been dead for 96 years.”

“Do tell.”

“He died of a virus, you know.”

“Who did?”

“Kafka. Tuberculosis at age 40.”

“Like poor Keats and his mother and his brother Tom.”

“You and your Keats.”

“He’s not my Keats. He’s posterity’s Keats.”

“Which brings me back to your novel. Or are you posterity’s Authorial Rabbit?”

Friend Titmarsh, sitting a physical distance away in my backyard, having brought his own food and utensils, even a glass, into which I am pouring jus de carotte, is alluding to my current struggle, a sequel to Ripped: A Gentle Fable of Homecoming, which I published in 2015. The sequel should be published this year, ‘should be’ the authorial hope, furry ears a-twitch. The new book again explores versions of the life of a certain boomer.

The boomer has aged, again, although the reference should not bring to mind those snow white boomers of Rolf Harris’, on Santa’s Australian run.

“Posterity could care less. And the here and now not much either. The question is for whom does the bell toll, in the sense not of identifiable individuals wondering if it tolls for them, but rather the question of the identity of individuals, any individual, all individuals, at any time.”

“Have you gone off your medications?”

“What I mean is what Wordsworth mentioned about his Prelude, his masterpiece of autobiography in poetry. I direct you to a fine review by Matthew Bevis of critical works on the great bard in Harper’s. Wordsworth spoke of himself as a writer as having ‘Two consciousnesses, conscious of myself / And of some other Being.’ That’s what I mean.”

“That’s clearer.” When Titmarsh used sarcasm it did not so much wither as wilt.

“Who are we?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“As persons. Some authors use nom de plumes.”

“Heaven forfend.”

“All of us are multiple personalities, with our multiple narrators, all crying to be heard, in the end none of whom is real.”

“It’s the confinement, the absence of friends.”

“Yes, partly true. In the company of friends we become happier versions of ourselves, usually happier, and that is gratifying, comforting.”

Titmarsh took up the theme. “And sometimes those versions become the mob. Shouting for the history’s failed despots and ideologies.”

“That too. You know, Wordsworth was a wild one, as Bevis’ review reminds us. He identified with his ruffian Peter Bell and knew the savagery of children. Bevis says that when Emerson visited the elderly Wordsworth, he encountered a disappointingly plain, unprepossessing narrow-minded old man disfigured by green goggles and felt he had been subjected to the unlovely sight of an individual who had become an institution. Mad, bad Lord Byron called him ‘Turdsworth,’ and his work ‘drowsy frowzy.’

“But Wordsworth’s mother described him as ‘stiff, moody and violent’ as a child, her only child to cause her anxiety. And others observed that child, ‘father to the man,’ in him all his life.”

The sun was getting hot. Titmarsh had placed his handkerchief over his head. He sipped his drink a bit desperately.

I chose to finish my sermon before suggesting we move to the shade: “Was it Oscar Wilde who said we needed a mask to tell the truth? Today I would just say we can become not only more interesting to ourselves and others than we think we are as we engage our many personalities, but also more selfless, more giving. And these days, all days, that’s a good thing.”