A Doe I Know (DIK — let’s call her Dee) and I, the Authorial Rabbit, have watched three older movies in our self-isolation that in their different tones offer artful, affecting and intelligent views on the passage of time, that new pandemic fascination.

The first was Academy Award Best Picture The Grand Budapest Hotel, released in 2014, directed by Wes Anderson, a masterpiece with a big cast of first-rate actors and clearly a tremendous crew.

The movie darkly, wittily satirizes the decline of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Its cinematographic language is a marvel. It jumps along like Bob Fosse or at least some dancer on cocaine, each scene a new farcical hilarity evoking the best choreography of the silent film era.

As with all satires, its real target is its own time, our time, and it is more relevant than ever after six years. It is set in the Republic of Zubrowka, redolent of many a tawdry post-empire, behind-the iron-curtain, runtish political concoction reeking of stagnant rot, corruption, income inequity and neglected lives.

A younger AR, a mere buck, had himself visited such locales, guided by Dee, who told him her own stories of earlier times, for she had been born in one of them and nearly starved there, the destruction and the long rebuilding of edifices and lives after a cataclysm whose origin lay in the hubris that never dies, only sleeps.

In GBH‘s putative narrator, an author who writes the hotel’s story through the life of its current owner, the film guides us to remember Stefan Zweig, author of Die Welt von Gerstern, in English The World of Yesterday.

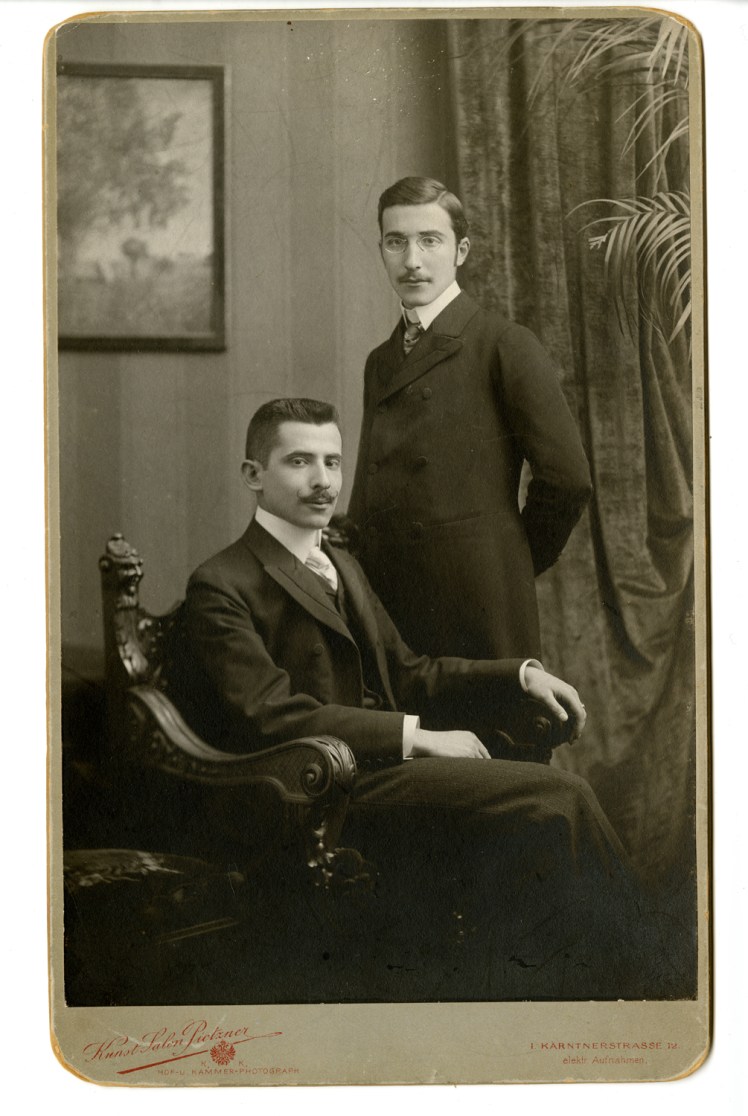

Stefan Zweig on the right, with his brother.

Stefan Zweig on the right, with his brother.

That world was Vienna where Zweig was born into a wealthy Jewish family and the Habsburg empire in its prime, so culturally rich and yet the fool’s paradise, as Zweig called it in retrospect, of the nineteenth and early twentieth century before WWI. The “golden age of security.”

Zweig was a highly respected and prolific author who took it upon himself to promote pacifism, pan-Europeanism, and other artists and intellectuals he esteemed and the value of a cultured life. He was not one of those many brainiacs who climbed on their imaginary iron horses and excitedly embraced German and Austrian militaristic patriotism at the start of WWI. Zweig considered nationalism in its narrow and nasty sense as the worst curse. After having to flee Vienna in 1934, he became a nomad, finally washing up in Brazil, where in 1942, his dream of a civilized world, that world of yesterday, brutally destroyed, he and his wife committed suicide.

Long after, the AR himself stood upon Stefan-Zweig-Platz in Wien, its small memorial to the great man, near the Himmelmutter Weg (Heavenly Mother Way) and its vineyards. Curiously, the AR had met a connection with that former time on another visit: no less than a descendent of the Habsburgs.

The AR and the von Habsburg were both seated at an outdoor table to watch a tableau vivant staged in a lake in Baden bei Wien, Vienna’s nearby spa town. The event was to celebrate the birth of Empress Elizabeth, aka Sissi, the gentleman’s great grandmother. His table colleagues referred to him as His Royal Highness. Herr M. von Habsburg was a friendly, cultured person, generous with his time and ideas, still sporting the distinctive rather French nasal accent of the old Austrian aristocracy.

The second movie was Pleasantville (1998, Gary Ross, Director), a charming send-up of the 1950s mindset in North America, along with a sharp and moving exploration of what it means to be free, freedom not in the current virus lock-down protestors sense of not wanting to be denied one’s pub experience or having to stay at home with the kids or having to wear a mask, but the existential freedom of being able to explore the full richness of life, with its creativity, its love, its danger.

Also a movie with a fine cast and production values, Pleasantville is about a Leave It To Beaver style of fifties eponymous television show where life is lived in black and white, another version of the golden age of security, except that the highest culture aspired to in Pleasantville is a pleasant unvarying routine. One thinks of Michael McClure’s comment about Ginsberg and company throwing down the gauntlet against another narrow, sterile and militaristic period, as referenced in a previous blog by the AR.

Colour, the symbol of freedom, is brought into the Pleasantville inhabitants’ lives by the intrusion from the future of a very modern brother and sister, the latter a selfish teen of strong sexual and peer-group impulses played by Reese Witherspoon, an actor of wonderful range and power.

At one point when tensions are running high owing to invasion by the moderns, and the old guard is frightened when the skin of some young people and a few older ones excited by new possibilities has changed from black and white into colour and their behaviour is becoming unpredictable, we see signs in windows saying No Coloreds Allowed.

Indeed, the button-down collars and lacquered-hair veneer of the fifties, like Zweig’s golden age of security, hid serious problems. Zweig’s memory of all classes in Austro-Hungarian society working harmoniously together, sharing their love of high-art, even if the lower classes could never attend the Burgtheater or the Oper, is surely a blindness of his class and time. Life on the farms and in new industrial factories was seriously hard. Likewise with the poisonous racial and poverty inequities of post WWI America.

The third movie was The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008, David Fincher, Director) about a man who is born old at the end of WWI and grows younger throughout the century, as his adopted parents, friends, his wife, his daughter, age and die around him. It was based on a 1927 story by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Its pathos is powerful, and its message of love and the necessity of developing the capacity for letting go is a spiritual complement to the other films. The Buddhists remind us that all is change, anicca in the Pali language of the Buddha: nothing is permanent or absolute, no matter how aggressively some leaders and propagandists rush to disguise, with their winners and losers creed, this central vulnerability of all lives on this planet. Only by mourning our loss, understanding that loss applies to all of us, accepting it, extending our compassion to all beings, can we gain our own and our planet’s health.

All your blogs are inspiring!

LikeLike